![]()

![]()

|

Wormwood is the Basis for a Cancer-fighting Pill |

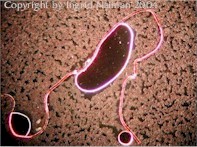

| Annual wormwood Artemisia annua L. |

Wednesday, November 28, 2001 Environmental News Network |

A nontoxic pill that could be taken on an outpatient basis to combat breast cancer or leukemia sounds like a fantasy, but the treatment is becoming a reality due to the investigation of a University of Washington research team into an ancient Chinese remedy for malaria.

Two bioengineering research professors at the University of Washington have rediscovered wormwood as a promising potential treatment for cancer among the ancient arts of Chinese folk medicine.

Research professor Henry Lai and assistant research professor Narendra Singh have exploited the chemical properties of a wormwood derivative to target breast cancer cells with surprisingly effective results. A study in the latest issue of the journal Life Sciences describes how the derivative killed virtually all human breast cancer cells exposed to it within 16 hours.

"Not only does it appear to be effective, but it's very selective," Lai said. "It's highly toxic to the cancer cells but has a marginal impact on normal breast cells."

Environmental risk factors for cancer are many. Lifetime exposure to the female hormone estrogen and estrogen-mimicking chemicals such as some pesticides and herbicides has been linked to an increase in breast cancer risk. In 1991, the International Agency for Research on Cancer classified the pesticide DDT as a possible human carcinogen, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has classified DDT as a probable human carcinogen.

The manufacture of PCBs, the oily liquids or solids used as coolants and insulators, was stopped in the United States in 1977 because of concerns that exposure increases the risk of cancers, but PCBs are still found in the environment.

Most Americans are exposed every day to air toxins emitted by motor vehicles, substances that the EPA says have been proven to cause cancer in humans. "Benzene, says the EPA, "is a known human carcinogen, while formaldehyde; acetaldehyde; 1,3-butadiene; and diesel particulate matter are probable human carcinogens." The EPA has now classified 1,3-butadiene, a gas used commercially in the production of resins and plastics, as a known human carcinogen.

The use of the bitter herb wormwood is nothing new. Used for centuries to rid the body of worms, it is also an ingredient in the alcoholic beverage absinthe, now banned in most countries.

Artemisinin, the compound that Lai and Singh have found to fight cancers, isn't new either. It was extracted from the plant Artemesia annua L., commonly known as wormwood, thousands of years ago by the Chinese, who used it to combat the mosquito-borne disease malaria. The treatment with artemisinin was lost over time but rediscovered during an archaeological dig in the 1970s that unearthed recipes for ancient medical remedies.

Now widely used in Asia and Africa to fight malaria, artemisinin reacts with the high iron concentrations found in the malaria parasite. When artemisinin comes into contact with iron, a chemical reaction ensues, spawning charged atoms that chemists call free radicals. The free radicals attack cell membranes, breaking them apart and killing the single-cell parasite.

About seven years ago, Lai began to hypothesize that the process might work with cancer, too.

"Cancer cells need a lot of iron to replicate DNA when they divide," Lai explained. "As a result, cancer cells have much higher iron concentrations than normal cells. When we began to understand how artemisinin worked, I started wondering if we could use that knowledge to target cancer cells."

Lai devised a potential method and began to look for funding, obtaining a grant from the Breast Cancer Fund in San Francisco. Meanwhile, the UW patented his idea.

The thrust of the idea, according to Lai and Singh, was to pump up the cancer cells with maximum iron concentrations, then introduce artemisinin to selectively kill the cancer.

In the current study, after eight hours, just 25 percent of the cancer cells remained. By the time 16 hours had passed, nearly all the cells were dead.

An earlier study involving leukemia cells yielded even more impressive results. The cancer cells were eliminated within eight hours. A possible explanation might be the level of iron in the leukemia cells. "They have one of the highest iron concentrations among cancer cells," Lai explained. "Leukemia cells can have more than 1,000 times the concentration of iron that normal cells have."

The next step, according to Lai, is animal testing. Limited tests have been done in that area. In an earlier study, a dog with bone cancer so severe it couldn't walk made a complete recovery in five days after receiving the treatment. But more rigorous testing is needed.

If the process lives up to its early promise, it could revolutionize the way some cancers are approached, Lai said. The goal would be a treatment that could be taken orally on an outpatient basis."

That would be very easy, and this could make that possible," Lai said. "The cost is another plus: At $2 a dose, it's very cheap. And with the millions of people who have already taken artemisinin for malaria, we have a track record showing that it's safe."

Whatever happens, Lai said, a portion of the credit will have to go to unknown medical practitioners, long gone now. "The fascinating thing is that this was something the Chinese used thousands of years ago," he said. "We simply found a different application."

Copyright © 2001 Environmental News Network Inc.

Remarks on the usage of this product

Material on wormwood as well as parasites on kitchendoctor.com

![]()

Bulletin

This press release has caused quite a stir in the herbal community. The article is a little misleading because Artemisia annua is not generally referred to as wormwood but rather Sweet Annie. The Chinese name is Qing hao. Though artemisinin is also found in other types of artemisia, the wormwood used to make absinthe was Artemisia absinthium.

Organic Artemisia annua grown in the U.S. from Chinese seeds

2 oz., alcohol extract

$

Because the article stressed the notion of pumping up the level of iron in the cancer cells, many have written asking how to do this naturally. The answer is, "I don't know," but I am working on a thesis that the iron concentrations in the cancer cells are not actually the type of iron needed to build good quality hemoglobin. More likely this is toxic iron, which unfortunately is exactly what is found in some blood building supplements.

The herb that is widely understood to help with proper iron assimilation is yellow dock. We provide this in glycerite form, using the laboratory methods described by Dr. Christopher. The fastest way I know to build up iron in the blood is with Tang Kwei Gin, a Chinese patent formula that we also carry though some breast cancer patients prefer not to take it. A more elegant formula is that put out by Floradix. It is called Iron + Herbs but it will take dozens of bottles of this product to give a result comparable to one bottle of our Yellow Dock or the Chinese Tang Kwei Gin.

Tang Kwei Gin150 ml, $

Foreign visitors to this site may wish to order Artemisia annua from:

Doctors For Life Pharmaceuticals

P.O.Box 1647

Kloof

3640

South Africa

(Tel) +27 31 7640443

(Fax) +27 31 7640440

http:// www.malarlife.dfl.org.zaHealth care pracitioners can order artemisinin from:

![]()

Much of the material on this site is historic or ethnobotanical in origin. The information presented is not intended to replace the services of a qualified health care professional. All products discussed on this site are best used under the guidance of an experienced practitioner.

We encourage patients and their friends and family to avail themselves of the information found on the Internet and to share their discoveries with their primary care practitioners. If there are questions about the suitability of a product or strategy, please have your practitioner contact the web hostess.

We are interested in feedback, clinical data, suggestions, and proposals for research and product development. While we naturally hope for the happiest outcome in all situations, the authors of this web site, webmaster, server, publishers, and Sacred Medicine Sanctuary are not responsible for the success, failure, side effects, or outcome of the use of any of the information or healing strategies described on this site.

Sacred Medicine Sanctuary

Copyright by Ingrid Naiman 2000, 2001, 2005

*The information provided at this site is for informational purposes only. These statements and products have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. The information on this page and these products are not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease. They are not intended to replace professional medical care. You should always consult a health professional about specific health problems.